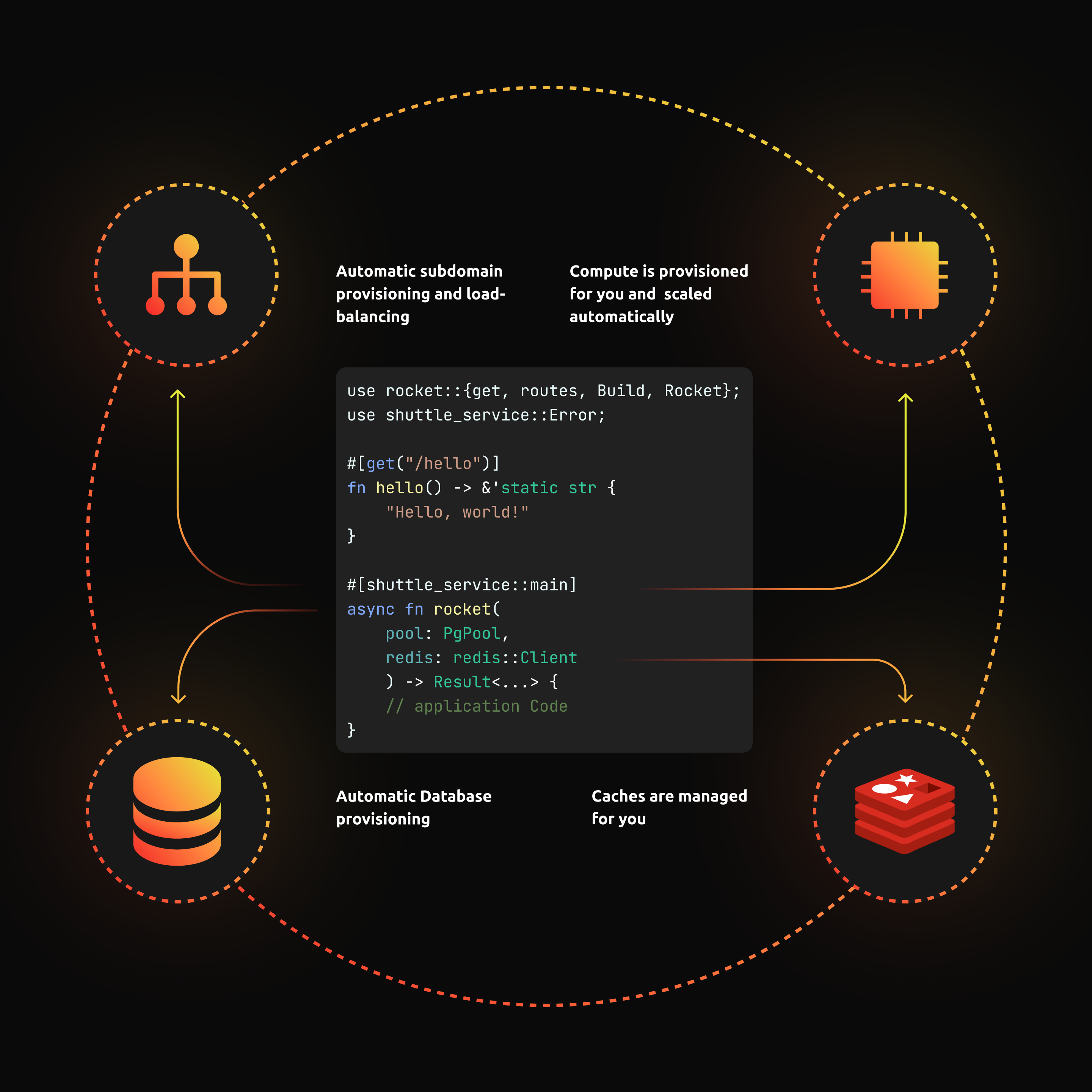

shuttle is a serverless platform built for Rust. The goal of shuttle is to create the best possible developer experience for deploying Rust apps. Also, shuttle introduces a new paradigm for developing on the cloud called Infrastructure From Code (IFC).

IFC uses application code as the source of truth for provisioning infrastructure. No longer are your applications and servers decoupled, the two go hand in hand. shuttle does this by doing static analysis of user code and generating the corresponding infrastructure in real time. A bit like this:

In the previous DevLog we started the journey of building the shuttle MVP. We went over the design and implementation of the cargo subcommand which deploys cargo projects to shuttle. This has been a race against the clock, so corners were cut and tradeoffs were made. A similar theme emerges in this DevLog which covers the deployment state machine. We're going to think about compiling and deploying user code, while also covering one of my favourite design patterns in Rust.

Deployment State#

shuttle exposes an HTTP endpoint under POST /deploy. This endpoint receives a series of bytes, from cargo shuttle, which correspond to a packaged cargo project (basically a compressed tarball with a bunch of .rs files).

The aim of the game, is to convert that series of bytes into a deployed web service - how do we go about doing that?

The deployment process is broken into 4 stages:

Queued- the cargo project is received and waiting to be compiledBuilt- the cargo project is compiled successfullyLoaded- the output of the compilation is loaded as a dynamically-linked libraryDeployed- the app inside the DLL is running and listening for connections

Then life happens so you need a couple more states:

Error- there was an issue anywhere in the build processDeleted- user-initiated deletion of the deploymentThis endpoint

Which corresponds to:

All this can be expressed nicely in an enum since all these states are mutually exclusive:

Even though we have a nice representation of our states - these states don't actually hold any data yet and the state transitions are not defined. We would like the DeploymentState to own all the data that corresponds to the specific stage in it's deployment. We'll create some structs to hold the data required for each stage.

First, the QueuedState just has a vector of bytes from the packaged cargo project that was received from cargo-shuttle:

When a deployment is queued, the shuttle build system writes the crate_bytes (just a tarball of a cargo project) to the file system. It then extracts the tarball and starts the compilation process by running cargo::ops::compile.

The output of the build process is an .so file which is held in the next stage - the BuildState:

So far so good. At this point we have a pointer to a compiled shared object file - next we need to load it into memory.

shuttle uses the libloading crate to dynamically load from a .so file a value of a type implementing the Service trait. The Service trait is code-generated for the user via the #[shuttle_service::main] annotation and it's how shuttle interfaces with client apps.

We keep the Library struct around since Box<dyn Service> is just a pointer to data loaded and managed by Library. Library going out of scope deallocates that data; meaning service will be pointing to deallocated memory hence we get a segfault. So it's important to keep Library around for the lifetime of the deployment.

Finally we find a free port, spin up a new tokio runtime (we keep the handle so that we can kill it in the future) and bind the service to the port. We'll be covering this stuff in depth on a future DevLog but if you're insatiably curious you can check out the source.

All of this is put into the DeployedState and we're done!

To tie it all together, we modify our initial DeploymentState own the various states corresponding to the stages of the deployment process:

We also wrote a really light impl to define the state transitions:

You'll also notice that there is no mutation happening here. We found it cleaner to simply drop the old state and construct a new one (although we did try).

Conclusion#

In the case of shuttle, using enum variants and structs to represent states in a state machine seemed like the natural thing to do. The states were distinct and clear, and for the most part the transitions are clean and self-contained.

So what do you think about enum variants as states in a state machine? What would you have done differently?

Next Steps#

In the next DevLog we'll be looking at the implementation of our reverse proxy and routing table - how we keep a ledger of deployed services and route network calls appropriately.

In the meantime, if you want to try out shuttle head over to the getting started section! It's completely free while shuttle is still in Alpha.