This post introduces some patterns and tricks to better utilise Rust's type system for clean and safe code. This post is on the advanced side and in general there are no absolutes - these patterns usually need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to see if the cost / benefit trade-off is worth it.

The new type pattern

The new type pattern provides encapsulation as well as a guarantee that the right type of value is supplied at compile time. There are several uses and benefits for the new type pattern - let's take a look at some examples.

Identifier Separation

A common representation of an identifier is a number - in this case let's use the unsigned integer type usize.

Let's say we have a function that receives an identifier for a User from a database by username. By using a unique username our API retrieves the identifier of the user:

fn get_user_id_from_username(username: &str) -> usize

Let's say we have a similar mechanism for another entity, Post.

If our application is performing operations involving posts and users, the logic can get in a mix:

let user_id: usize = get_user_id_from_username(username);

let post_id: usize = get_last_post();

fn delete_post(post_id: usize) {

// ...

}

delete_post(user_id);

Here get_user_id_from_username and get_last_post both return usizes while delete)_post also takes a usize. In this code we can accidentally call delete_post with a user_id, there's nothing in the type system that would stop us from doing that.

To differentiate between these two identifiers we can use the new type pattern:

The new type pattern boils down to creating a new tuple struct with a single item, in this case usize

struct UserId(pub usize);

Now we can change our library definition to return a UserId instead of usize

fn get_user_id_from_username(username: String) -> UserId {

let user_id: usize = ...

UserId(user_id)

}

Doing similar for the posts system with a PostId, when now compiling we get an error on when calling get_post.

|

14 | get_post(x);

| ^ expected struct `PostId`, found struct `UserId`

The new-type pattern enforces type-safety at compile time without any performance overhead at runtime.

Re-adding functionality to our type

After creating this new wrapper type, we may need to implement some of the behaviour of the type it is encapsulating to appease our compiler. For example consider a set of 'banned' users:

let banned_users: HashSet<UserId> = HashSet::new();

The above doesn't compile because our new type UserId doesn't implement equality and hashing behaviour whereas usize did. To add these traits back we can use the inbuilt derive macro, which generates implementations for our struct based on the single and only field.

#[derive(PartialEq, Eq, Hash)]

struct UserId(usize);

And we're good to go!

Contract based programming in Rust / sub-typing

The new type pattern can also be used to constrain types to only take 'valid' values.

In the above example we used a wrapper type to enforce flow of values, this method also enforces the content of the value. In our application we only want usernames to contain lowercase alphabetic characters. Wrapping over String we can do this:

struct Username(String);

The only way to create a Username is using the TryFrom trait.

impl TryFrom<String> for Username {

type Error = String;

fn try_from(value: String) -> Result<Self, Self::Error> {

if value.chars().all(|c| matches!(c, 'a'..='z')) {

Ok(Username(value))

} else {

Err(value)

}

}

}

This implementation returns a new Username if all the characters are lowercase. Else the string is returned and can be reused in logic possibly displaying an error.

As the string field is private a Username cannot be created with Username(my_string). It also cannot be modified by outsiders and invalidate our contract.

We can now use this structure as an argument to our API.

fn create_user(db: &mut DB, username: Username) -> Result<(), CreationError> {

// ...

}

Since the username is validated to be lowercase ahead of time, the create_user function doesn't care about whether the username is valid inside in its own scope.

This can lead to easier error handling. CreationError doesn't have to include a variant for the if the username has invalid characters.

Although the only safe way to construct if through the validator TryFrom trait, the Username can be created through unsafe transmute (casting the bits of one value to the type of another without checks). This is normally fine though as with unsafe you are introducing undefined behaviour anyway.

let string = String::new("muahahaha 👿");

let bad_username = unsafe { std::mem::transmute::<String, Username>(string) };

dbg!(bad_username);

Wrapping vs canonical type

Our wrapped type is great from the outside, however we are relying on logic internal to the type to validate our contract.

If we want to we can be really drill down on the structure of our username. Here we also enforce that the username has to be between four and ten letters.

#[rustfmt::skip]

enum Alphabet {

A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H,I,J,K,L,M,N,O,P,Q,R,S,T,U,V,W,X,Y,Z

}

enum Username {

FourLetters([Alphabet; 4]),

FiveLetters([Alphabet; 5]),

SixLetters([Alphabet; 6]),

SevenLetters([Alphabet; 7]),

EightLetters([Alphabet; 8]),

NineLetters([Alphabet; 9]),

TenLetters([Alphabet; 10]),

}

Even though there is no way to make an invalid username (except for unsafe) this is a little over the top 😂. In some edge cases it can be beneficial but in the example above this is clearly overkill.

Working with foreign traits on foreign types

Traits are great. They can be defined on structs and enums, but you may run into some issues when implementing a foreign trait on a foreign type.

This is by design, and here's why:

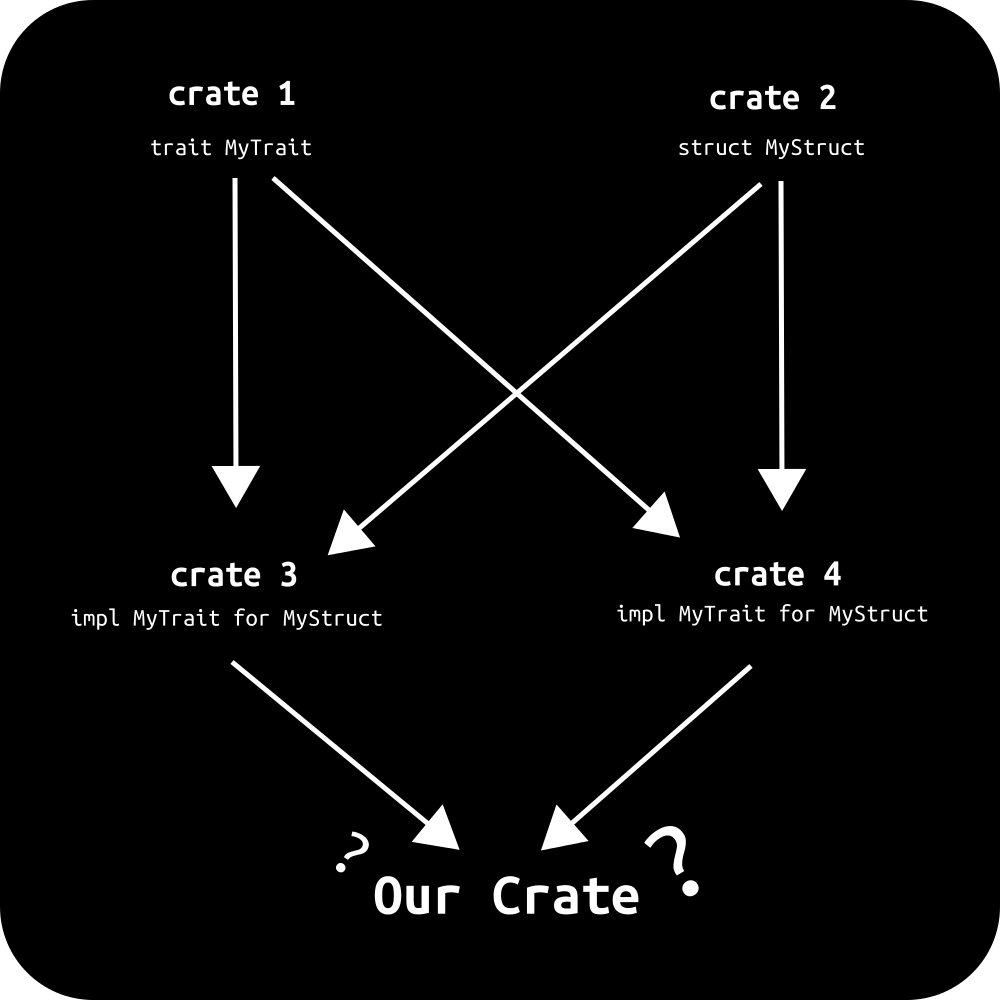

In our crate the compiler doesn't know when calling MyTrait methods on MyStruct whether to use the implementation defined in crate 3 or crate 4! Rust has a set of orphan rules to prevent this situation from happening.

In the situation where you'd like to implement a foreign trait on a foreign type - the 'new type' pattern can come to the rescue yet again:

// lives in crate X

trait ToTree {

// ...

}

fn very_useful_function(something: impl ToTree) -> () {

// ..

}

// Our crate

struct Wrapper(pub crate_y::MyType);

impl ToTree for Wrapper {

// ...

}

// Yay

very_useful_function(Wrapper(foreign_value))

One of the gotchas with this is that you have to manually implement the trait. You can't use derive macros, e.g. #[derive(PartialEq)] and reach through to the declaration of the wrapped type and read its declaration. You also have to make sure that you can properly implement the trait on the item. crate_y::MyType might hide information needed for the implementation 😕.

Ok - enough with the new type pattern. Let's leave it for a minute and look at some other tricks when working with types in Rust.

Using either to unify different types

Sometimes we have a case where we have a complicated data type

enum PostUser {

Single {

username: UserId

},

Group {

usernames: HashSet<UserId>

}

}

We'd like a method that returns an iterator, but we're stuck since we either return a single once iterable (std::iter::Once) or an iterator over a hashset. These iterators are different types and have different properties, so Rust doesn't like when we try to build a function returning both.

A Rust function / method can only return one type:

impl PostUser {

fn iter(&self) -> impl Iterator<Item=&UserId> + '_ {

match self {

PostUser::User { username } => std::iter::once(username),

PostUser::Group { usernames } => usernames.into_iter(),

}

}

}

The following will fail because the match arms have different types.

|

17 | / match self {

18 | | PostUser::User { username } => std::iter::once(username),

| | ------------------------- this is found to be of type `std::iter::Once<&UserId>`

19 | | PostUser::Group { usernames } => usernames.into_iter(),

| | ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ expected struct `std::iter::Once`, found struct `std::collections::hash_set::Iter`

20 | | }

| |_________- `match` arms have incompatible types

|

= note: expected struct `std::iter::Once<&UserId>`

found struct `std::collections::hash_set::Iter<'_, UserId>`

The either crate offers a general purpose sum type that implements many traits. Using either::Left for the once iterator and either::Right we can build two iterators into what Rust considers as a single type.

impl PostUser {

fn iter(&self) -> impl Iterator<Item=&UserId> + '_ {

match self {

PostUser::User { username } => either::Left(std::iter::once(username)),

PostUser::Group { usernames } => either::Right(usernames.into_iter()),

}

}

}

We could have instead boxed the results and returned Box<dyn Iterator<Item=&UserId>>. The benefit of using either is that it uses static dispatch rather than dynamic dispatch. enum_dispatch has good performance comparison for using static dispatch over dyn so if you are on a critical hot path, and you know all the returned types it is faster to use enums to unify types rather than dynamic trait dispatching.

Extension traits

When creating a library we may add some functions for working with existing types (whether in the standard library or a different crate).

Let's say we are writing a library on top of serenity which has models for discord servers (discord refers to them as guilds).

Let's write a helper function that gets the number of channels in a Guild.

async fn get_number_of_channels(

guild: &serenity::model::Guild,

http: impl AsRef<Http>

) -> serenity::Result<usize>

When calling the function we have to pass the guild as the first argument.

let guild: serenity::model::Guild = // ...

get_number_of_channels(&guild, client);

But from a design perspective we might prefer to use member notation instead: guild.get_number_of_channels(client).

We can't use add a direct implementation for a type defined outside our current crate.

/ impl serenity::model::Guild {

| fn number_of_channels<T: AsRef<Http>>(&self, http: T) -> serenity::Result<usize> {

| todo!()

| }

| }

|_^ impl for type defined outside of crate.

To define an associated method on a type outside the crate we must instead make an intermediate 'Extension' trait:

trait GuildExt {

fn number_of_channels<T: AsRef<Http>>(&self, http: T) -> serenity::Result<usize>;

}

impl GuildExt for serenity::model::Guild {

fn number_of_channels<T: AsRef<Http>>(&self, http: T) -> serenity::Result<usize> {

// ...

}

}

Using the intermediate trait the compiler can reason about when the method exists. To use the method syntax and show the compiler that the extension exists we must import the trait into our scope:

use crate::GuildExt;

let guild: serenity::model::Guild = // ...

let number_of_channels = guild.get_number_of_channels(client);

This pattern is used in the futures crate with the FutureExt trait.

Here using the trait FutureExt provides additional methods to the existing Future trait in Rust's standard library. Aside from syntax aesthetics, it becomes much easier to find object-specific functions when using an IDE.

You can use the easy_ext for doing this pattern on a single type without having to write the trait / trait definition is generated for you.

Conclusion

We saw how we can use various patterns like the new-type pattern and extension pattern to make our Rust code more ergonomic and take advantage of the type system and compiler to write better code. There is a great book out on Rust design patterns which covers some of these and many more patterns in Rust. What are your favourite design patterns in Rust? Let us know and we'll cover them next time!