Introduction#

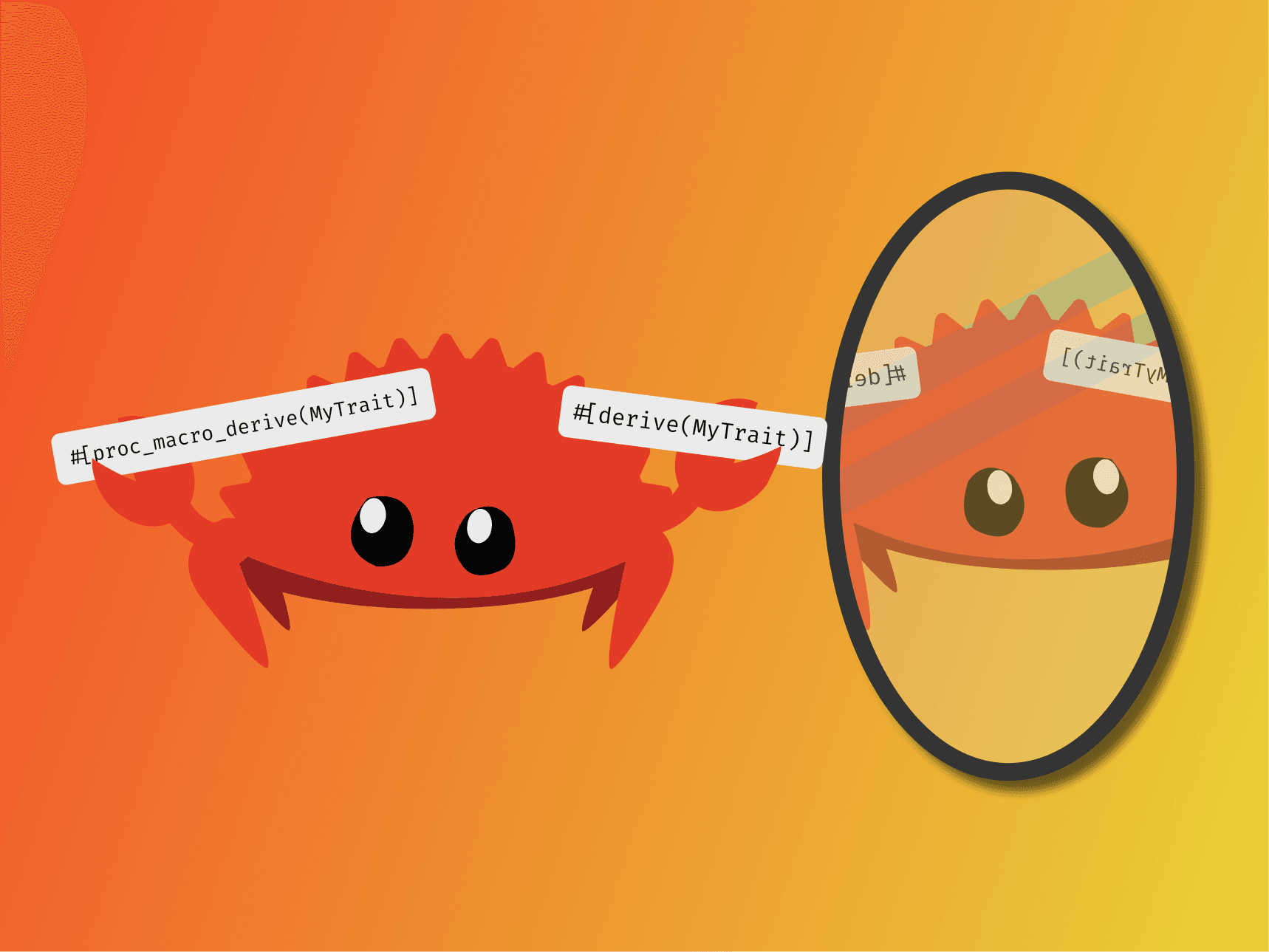

Procedural macros are one of the more complex but powerful parts of Rust. For me, it's one of the features that really sets Rust apart from other languages. If you have ever seen this syntax and left scratching your head, then this post is for you:

This article will cover the concept of macros and some interesting use cases, and you certainly don't need to be a Rust expert to follow along. However, the example section assumes you have written some Rust (if let , struct, trait etc).

In this post we'll compare how Rust's compile time, token based approach to object reflection is different to the approach in JavaScript's runtime approach to reflection.

What are Rust macros?#

Macros are a way of generating Rust code. They use tokens which are small sections of syntax / grouped characters. Keywords, identifiers and operators are examples can be considered as tokens. Token streams are vectors / ordered collections of tokens. In Rust, some tokens are grouped together and thus the stream is not always flat.

Macros take an input token stream and output another token stream. Macros are expanded at compile time so the output is checked syntactically and type checked. They are very powerful, so it's important to use them in a way for programs to still be understandable and maintainable.

Rust offers macro_rules! for creating macros using a pattern matching syntax that's bespoke to Rust. These are currently limited to just expression and statement invocations using my_macro! syntax. An example of an expression based macro is println!. Designing a function to print results to the terminal difficult to get right using just a function. Instead, it is implemented as a macro. This is very powerful, for example this allows writing a formatting string that interpolates variables in the scope (e.g. println!("{my_var}");). Also, as the input for macros is just a token stream, it is up to the macro to decide what commas mean and so println! arguments act variadic-ly.

macro_rules! are easier to get started with as they can be written and used anywhere inside the same crate. However, as we'll see they only work for user token inputs (not on existing items) and their pattern syntax is limited. In this article we'll be focusing exclusively on the more advanced procedural macros.

Procedural macros#

Compared to macro_rules! procedural macros are much more powerful in that they process token streams using Rust code instead of just using pattern matching:

Procedural macros are different to macro_rules! in that they can additionally work on the tokens of existing structures. This includes fn ,trait , struct and enum declarations. They also require creating a separate crate for the function. This article will walk through all the steps and file structure required to add a proc (from "procedural") macro to a crate.

Runtime reflection and JavaScript#

Before we start with writing procedural macros, let's take a look at closely related concept called reflection, what reflection is and how it is implemented in the JavaScript language. Reflection refers to code that may introspect and generate its own structure and behavior. There are various points to introspect such as the name of declarations, the structure of fields. In the following example we will be looking at the fields of an object in JavaScript.

JavaScript objects can be inspected at runtime. There are no fixed structures in JavaScript. Every object can have properties added or removed (unless sealed). On the other hand Rust structures are static, that is they are determined at compile time. Rust packs field data together to build structures and turns keys into offsets in memory. The actual fields, the count, the names are all lost at runtime under regular operation. On the other hand JavaScript objects at the surface level are all maps from keys to other JavaScript values. The names of properties are kept in memory at runtime. In Rust the rough equivalent type of a JS object would be: HashMap<&'static str, Box<dyn std::any::Any>> (ignoring object prototypes).

Our reflection example#

In our first example we have an array of JavaScript objects:

In our app we want to serialize this list to send it over the wire or to store locally in the browser. Our first instinct is to use JSON, but however we would ideally like a more space-efficient. We can take advantage of the fact that every object in the list has the same keys, we can take advantage of this and not serialize the keys over and over again. Another invariant we can take advantage of is that these objects are shallow (not nested) values with types which are known beforehand.

We can write a function that:

- Encodes the length of the array

- Investigates the properties of the first objects (as the list is homogeneous, these facts apply to all objects in the array)

- Loops over items in the array

- Reads each field name in the object

- Based on the type, encodes the value into a low level representation

Here with Object.entries we can inspect the shape of an object at runtime. Using the typeof operator we can get the type of the value. (Again assuming that all objects have the same type):

Assuming homogeneity of elements in the array, we can do reflection only once outside the main loop. Another fact is the fields are serialized in the same order. If we did reflection on each we would have to be careful of retaining the order. Objects keys are in order of declaration, so this can cause some problems with a subset of the reflection API:

We also use Reflect.get to get a property under a given string key (item[name] is equivalent).

The idea of the example is not to show how to do low-level byte conversion in JavaScript but to show how you can mix in the the introspection logic. As we will see later runtime reflection is very difficult to do in Rust as there are no equivalent

Object.entries,Reflect.getfunctions or atypeofoperator in the language.

Now that we can serialize the array with arrayToString(countries), we want a way to reverse the process!

However, the deserialization process be a little problematic, reflection in JS can only be done when we have a existing structure in inspect. As there are no type/shape declarations in plain JavaScript, there is no reference of the shape of the object we want to deserialize our serialized string into.

If we were using JSON we would be okay as the keys are embed into the serialized format, in our example we don't save the keys. Instead we can send a representation array of the key type pairs we want the objects to look like. Using fields and with a bit of conversion from our low level formatted string we have the following:

Here we're using another part of reflection Reflect.set which allows us to set a property of an existing object based on a string key (name).

Problems with reflection in JavaScript#

The arrayToString function assumes that the caller has passed a standard array where every object has the same type. Reflect.get will fail at runtime as if the property doesn't exist. The downside of this is that both the dynamic property lookup and null check is expensive at runtime.

One way to catch property errors ahead of time is to use a type system on top of JavaScript such as TypeScript.

Writing a Rust procedural macro#

To get started, if you are not already in a cargo project you can create one with cargo new <name> command. Before we start generating code we should declare a trait as a target for our macros output.

The Binary trait#

First, we need to create a trait which describes the requirements for serializing and deserializing objects - let's call this the Binary trait. Serialization will require adding information on the structure into a buffer. Deserialization will require pulling from an iterator (which iterates over bytes of a serialized buffer) and producing a term of Self. We will assume the deserialize input is well-formed and panic at runtime rather than proper handling with Result when deserializing.

We can implement the Binary trait for the primitives that will be in our structures:

The problem#

Next we would want to implement the same logic for structs.

We could implement Binary for Country, writing a bespoke implementation for it manually:

This is great and we have our desired functionality. In this code we have to be careful we serialize and fields in the same order. Writing this impl block out for many structs with many fields would get tedious. If we add another struct we want to be serializable we don't want to have to have to copy the implementation over.

With some idea of the code we want to write, we can get Rust to generate the above code for us using just the information in the struct definition. This is where proc macros come in...

Procedural macro time!#

Now we know what code we want to generate, we can write some Rust code to handle a structure and generate the an output token stream.

Rust procedural macros require their own crate for their definition due to constraints on how they are compiled. The unofficial Rust convention for derive macros is the name of trait or crate name + derive. So let's run the following from our current folder cargo new --lib binary-derive. We need to let cargo know that this crate is a proc macro by defining it in its Cargo.toml. We'll also add the dependencies syn for parsing the contents of our structure and quote for generating the output:

In our macro we want to parse the input into a structure that we can read information from. In the below we can read .fields directly without having to understand what tokens refer to field names and such.

Our macro starts with a pub function with an attribute #[proc_macro_derive(Binary)] to show this is the derive macro for Binary. In the code we use two iterators. One that generates serialize calls on fields and one that deserializes fields and assigns them to fields. Throughout we use quote! (which yes is another macro 🤯). With quote we can describe the tokens we want to generate in a declarative form exactly the same as Rust's syntax. The expanded variable is code that is a copy of the above however using the hash # character we can specify variables we want to interpolate. For example our struct name is interpolated into impl Binary for #name. We then interpolate our iterators. Using parenthesis and asterisks we specify run through the items from the iterator with a separator in between. In the first case the serialize call statements are separated with semicolons #( #serialize_fields );*.

Using the procedural macro#

With our macro written, we include our crate using a path dependency

Similar to a function or other items we can import and reference the macro. It does not clash as macros and types have different name-spaces therefore we can have a macro and trait with the same name in the scope. (traits exist in the type namespace). We can tell the compiler that we want to generate code for Country using the #[derive(...) attribute on our struct.

cargo expand-ing our macro (optional)#

We can debug the output by installing cargo-expand (cargo install cargo-expand). Running cargo expand we see the result which is the automatic generated what we wrote manually:

cargo-expandrequires Rust nightly and can require runningcargo cleanif switching back and forth between stable.

Alternatively, adding eprintln!("{}", expanded) to the end of your macro code and then running cargo check also helps for debugging. The output is not as readable but it works for malformed token streams.

We can now emulate what we were doing with JavaScript arrays using regular generics and trait logic in Rust:

Considerations#

As procedural macros are expanded at parse-time, there is no type information available to the macro. We can examine type references syntactically but you can't rely on the characteristics as the following is valid Rust code:

Additionally, macros can result in increased compile time. When building the crate all the macros need to be run and the output token streams need to be parsed.

Another problem is that the trait and its corresponding macro are split across crates. If like me you like keeping similar logic together then you might be a bit annoyed that it is impossible to have the trait definition and macro automatic implementation in the same file. The other difficulty is publishing the crate to crates.io (with cargo publish). For your crate to work its derive macro crate also needs to be published. If you update the trait and the macro you must first release the proc macro crate and then afterwards update the dependency version before publishing the main crate.

syn-helpers#

syn-helpers is a framework I have been working to abstract common derive patterns. Our short example works great for our Country struct. However our macros should but doesn't currently work across enums, items with generics, etc. With syn-helpers it abstracts the item the derive is on and gives a really simple way to add logic to fields. It's still a work in progress but not all proc macros need long and complex implementations.

Inner annotations#

Sometimes we want to have some custom behavior for a field. Rust allows for writing attributes in lots of places. The attribute can be read from the syntax tree that syn parses and are simple to lookup. They can contain token stream arguments if even more information needs to be given to the macro.

In our example if there was a field we didn't want to end up in the output and that could be generated at runtime using default. We could add the following attribute and in the logic of the macro doing some different handling here.

Just remember when doing so to register with Rust that the attribute belongs to the derive macro by registering attributes in the proc_macro_derive attribute. E.g. #[proc_macro_derive(Binary, attributes(serialization_skip))]

Conclusion#

Performance characteristics#

As code is generated at compile time. It can be faster than having to do the work at runtime. Compared to JavaScript reflection, the properties are known at compile time, and we can read them using memory offsets. We won't cover it here as it is difficult to benchmark the difference between JavaScript's runtime reflection and Rust with proc macro compile time reflection, without the results including other differences in the languages.

Real world procedural macro examples#

Proc macros are used throughout Rust. Most standard library derives are proc macro could be implemented as proc macros.

Serde#

Serde, a serialization and deserialization library is a prime example. It is feature-complete and supports a bunch of different serialization formats like JSON, YAML, etc.

Shuttle#

Shuttle which is a Rust-native cloud development platform uses procedural macros to define how a service runs and what features it needs. It works a bit differently using attribute macros (as opposed to the derive macros we used in our example) which work on more items that just structs and enums. They allow complete rewrites of token streams as opposed to just generating additional code. Here macros enable users to define how the service runs along-side business logic, rather than having to manage configuration files separately. Long live infrastructure for code!

In summary procedural macros are good for#

- Common operations over structures, reducing boilerplate

- Performant reflection. Reduced worked compared to dynamic/runtime lookup

- Type checked, we can't run code that look on non-existent fields

Hopefully if you were previously perplexed, this post cleared up the why's and how's of procedural macros. If you make anything cool with Rust and need a place why not try Shuttle!

This blog post is powered by shuttle! If you have any questions, or want to provide feedback, join our Discord server!

Shuttle: The Rust-native, open source, cloud development platform.#

Deploying and managing your Rust web apps can be an expensive, anxious and time consuming process.

If you want a batteries included and ops-free experience, try out Shuttle.